LLM intelligence is not inferior to human thinking

They both run the same basic prediction algorithm

Listen to a summary of the article here:

Cogito Ergo BS

Raise your hand if you think human intelligence is something special, something uniquely creative that large language models can never duplicate? I see that most of you did. Cool, cool. Now ask yourself, how do you know that for sure? Did you ever take a course on human intelligence? Or do you just feel the magnificence of the human mind in your bones?

Human intelligence is much closer to GPT 5.2 (or other LLMs) than you think. And this realization has implications.

In 2004, Jeff Hawkins (the founder of the Palm Pilot and neuro thinker and researcher) made a bold prediction in his book, On Intelligence:

Intelligent machines would emerge not from programmed rules, but from systems optimized for prediction.

Twenty years later, large language models have vindicated half of his thesis while exposing awkward truths about both artificial and human intelligence.

The convergence is substantial but incomplete, and understanding the difference matters even more than the similarity.

The Algorithm We Share with AI

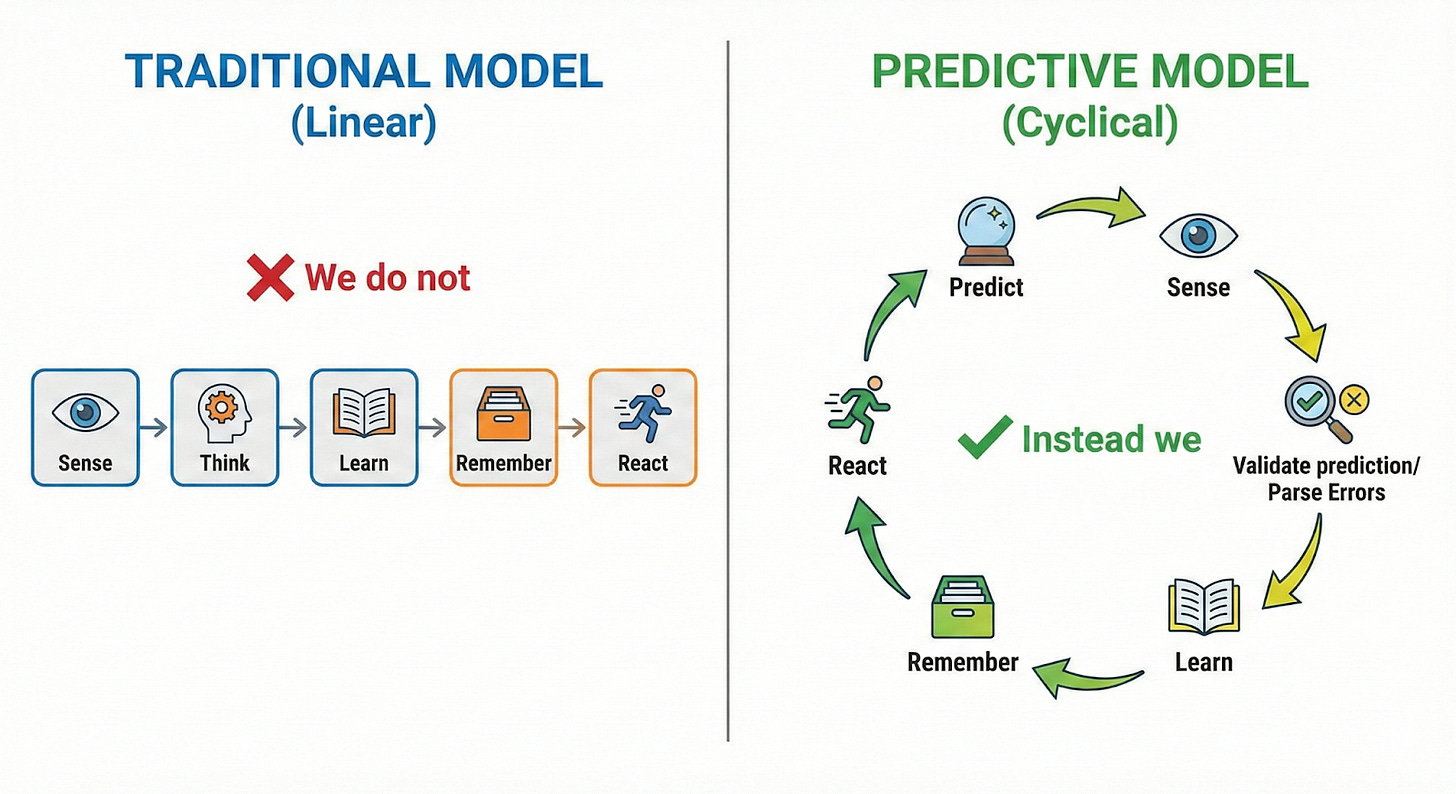

The human neocortex is fundamentally a prediction machine, not a cogitation engine, as we have been told all of our lives. This is measurable neuroscience. A 2023 study in the Journal of Neuroscience discovered dedicated prediction-error neurons1. These are neurons that fire when we notice differences in what our brains predicted vs. what our senses absorb in the auditory cortex. They remain completely silent until expectations are violated.

Yes, your brain and its subsystems have a ‘prediction difference’ engine - we have specialized hardware for prediction. Different neuronal populations fire for different error types: timing violations, volume mismatches, and pitch deviations. The brain constantly generates predictions about what should happen next, compares them to reality, computes the error, and updates its memory and model. This cycle runs at roughly 10Hz across sensory systems.

Large language models do something remarkably similar. During training, GPT-style transformers see a sequence of tokens, predict the next one, compute the prediction error (cross-entropy loss), and update their weights. Repeat this 10^12 times across trillions of tokens, and sophisticated behavior emerges, not from explicit programming of grammar rules or reasoning patterns, but purely from optimizing prediction accuracy.

This empirical alignment between our biology and LLMs is striking.

MIT research in 2024 showed that GPT models trained on as little as 100 million words (roughly what a 10-year-old child has heard) predict human fMRI responses in the language-selective cortex with r=0.65 correlation2. Google’s comparative study found that Whisper’s speech encoder activates superior temporal gyrus patterns, while its language decoder mirrors Broca’s area activity 200-500ms later, matching the brain’s sensory-to-semantic processing sequence. Multiple studies from 2021-2024 consistently show that better next-word prediction correlates with better brain alignment.

This convergence suggests prediction-based learning isn’t just one way to build intelligence. Instead, it may be the fundamental algorithm. Evolution and engineering, under entirely different optimization pressures, independently arrived at hierarchical systems that learn by iteratively predicting and correcting.

De-Mythologizing Human Cognition

If LLMs produce intelligent-looking behavior purely through prediction optimization, what does that say about human creativity and reasoning?

We mythologize human thinking as something fundamentally different from pattern matching. We invoke inspiration, intuition, understanding—as if these transcend statistical learning. But contemporary neuroscience suggests our “creative insights” may be sophisticated prediction errors. When you have an “aha moment,” prediction-error neurons are firing intensely. When you struggle to recall a memory, you’re not accessing a file, you’re reconstructing a prediction based on fragments. Even rote memorization is prediction-based: learning that Paris is the capital of France means learning to predict “Paris” when prompted, with minimal error.

This doesn’t diminish human intelligence. It clarifies it. The brain’s 16 billion neurons and 100 trillion synapses running on 20 watts are doing something computationally extraordinary with prediction as the core algorithm. The question isn’t whether we’re “just” prediction machines, it’s what prediction-based learning can achieve given sufficient architecture and data.

LLMs help us see this clearly, precisely because they lack so much. They have no body, no continuous learning, no lived experience, no self-narrative spanning decades. Strip all that away, and what remains? A prediction engine that can still reason, generalize, and surprise us. This suggests the gap between human and artificial intelligence may be smaller in some dimensions and larger in others than we assumed.

The Gaps That Matter

This is not to say that we are exactly like LLMs. There are real and consequential differences. The human brain operates continuously, learning from single examples through immediate synaptic plasticity. LLMs train in massive batches and then more or less freeze. The brain tests its predictions through embodied action: reach for a cup, feel the weight, update motor models. LLMs never close the sensorimotor loop. At least not yet, since they are disembodied.

Most critically, human cognition includes layers absent from current LLMs: phenomenal consciousness, persistent self-narrative, emotional valence that weights memory formation, learning across vastly different timescales simultaneously. A traumatic event changes you after one exposure. A skill develops over years. LLMs have fixed context windows and no mechanism for the kind of long-term memory consolidation that builds a coherent self over decades.

The brain also runs six orders of magnitude more efficiently: roughly 10^15 operations per watt versus 10^9 for LLM inference. This isn’t just an engineering detail. It suggests that neurons are using computational tricks we haven’t yet discovered.

Prediction Creates Emergent Behavior

This prediction-based convergence carries a serious implication: we may not be able to predict what capabilities emerge when scaled.

If “understanding” and “reasoning” emerge naturally from hierarchical prediction rather than being explicitly programmed, what other capabilities might emerge unexpectedly? The brain’s prediction architecture yielded consciousness, theory of mind, and self-awareness. And these are features nobody would predict from studying individual neurons. We don’t know what the LLM equivalent might be.

This demands both limiters and enhancers. The brain has inhibitory neurons, neuromodulators, and sleep cycles that consolidate some memories and discard others. LLMs currently lack analogous mechanisms for selective forgetting, attention filtering, or dynamic capability modulation.

If we’re going to push prediction-based systems toward greater capability, we should understand which architectural features enable beneficial emergence versus runaway behavior. The brain’s hierarchy isn’t just deeper—it includes feedback loops, lateral inhibition, specialized prediction-error pathways, and mechanisms for detecting uncertainty. These aren’t decorative features. They’re control structures.

Humility and Opportunity

The brain-LLM parallel should inspire humility in both directions. For AI research: we’re not close to replicating human intelligence, and we may not even be asking the right questions yet. For human cognition: our creativity and reasoning, while remarkable, may be less mystical and more algorithmic than we’d like to believe.

The risk is premature certainty in either direction. Claiming LLMs work “just like brains” misses crucial differences in implementation and capability. Dismissing the parallel as superficial ignores that prediction-based learning appears to be a universal algorithm for intelligence, regardless of substrate.

Hawkins was right that prediction-based systems would enable intelligent machines. What he couldn’t foresee was how much those machines would teach us about the prediction engine between our ears and how much both still have to learn from each other.

Understanding the limits of that principle matters as much as celebrating its power.

Bonus 1: Brain techniques that haven’t been tried in LLMs yetCurrent LLM research focuses heavily on attention mechanisms and reinforcement learning. But neuroscience offers a much richer toolkit that we’ve barely begun to explore:

Memory attenuation: The brain doesn’t store everything. It strengthens memories through sleep consolidation, weakens irrelevant details, and actively suppresses competing associations. LLMs treat all training data almost equally even with reinforcement learning. What if they had sleep cycles? What if they could forget?

Predictive filtering: The brain filters sensory input before prediction—you don’t consciously process every photon hitting your retina. Visual attention pre-selects what gets predicted in detail. LLMs currently attend to everything in their context window with equal potential weight.

Error-type specificity: The brain has different neurons for different prediction errors—timing versus content, expected versus unexpected novelty, reward versus punishment. LLMs have one monolithic next-token objective. What would specialized error channels enable?

Hierarchical timescales: V1 predicts edges at 10-100ms. Prefrontal cortex predicts events at seconds-to-minutes. The brain natively operates across timescales. LLMs have fixed context windows. Multi-timescale prediction might unlock longer-horizon reasoning.

Active & interventional inference: The brain doesn’t just predict—it acts to make predictions come true or gather information to reduce uncertainty. LLMs are passive predictors although tool calling simulates this. Embodied AI research is beginning to explore this, but we’re still early.

We’re perhaps 5% into understanding what prediction-based architectures can do. The brain represents 4 billion years of evolutionary R&D on prediction optimization. We’ve been doing it intentionally for about five years. The learning curve ahead is steep.

Bonus 2: AGI prediction

Most of the brain’s development arrives not from “thinking” ie learning to solve the hardest math problems, but from managing the body and outside stimulus. The first milestones in a child’s life are from managing vocal cords, managing limbs, and understanding the meaning in faces, etc. AGI arrives much faster as soon as we give AIs a body to sense the environment.

So watch you Waymo cars. They’re gonna come for us first :-)

🔍 Want to dive deeper?

Check out our book BUILDING ROCKETSHIPS 🚀 and continue this and other conversations in our 💬 ProductMind Slack community and our LinkedIn community.

🎧 Prefer to listen? Check our podcast below ↓

🎥 YouTube → Click Here

🎵 Spotify → Click Here

🎙️ Apple Podcasts →Click Here

Audette, N. J., & Schneider, D. M. (2023). Stimulus-Specific Prediction Error Neurons in Mouse Auditory Cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 43(43), 7119–7129. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0512-23.2023

Hosseini, E. A., Schrimpf, M., Zhang, Y., Bowman, S., & Zaslavsky, N. (2024). Artificial Neural Network Language Models Predict Human Brain Responses to Language Even After a Developmentally Realistic Amount of Training. Neurobiology of Language, 5(1), 43–63.